Decades of Change: A Review of 40 Years of Title IX

Although written during the date provided, this article was republished during 2020 by Nicolas Gorman to put it on the website. The author is unknown.

Most women couldn’t play sports. They could be cheerleaders or take Home Economics, and the select few who were allowed to play had to raise all of the money to maintain their teams, even making their own uniforms because their schools refused to supply any funding. At some schools girls were even barred from publicizing their sporting events.

Then on June 23, 1972, Title IX was signed into law by President Richard Nixon. The new law required that “no person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

While the law’s effects were most visible in equality for women’s athletics, the law also improved accessibility for women to higher education and opportunities to take math and science classes, as well as recourse for sexual harassment.

A lot has changed since the early 1970s, but some remember what it was like to grow up with the discrimination Title IX prohibited.

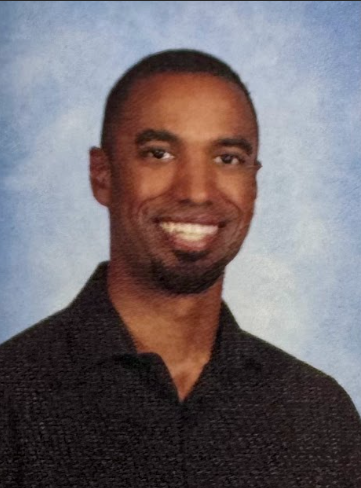

“It’s amazing what it’s done” physical education teacher and former varsity football coach Mike Smith said. “When I went to high school, girls didn’t play sports.”

The law created some problems, such as finding funding to create women’s sports, Smith said. But he said the good outweighed the bad.

At its inception in 1972, women made up only 7.5 percent of high school athletes and 15 percent of college athletes. Now that number is over 40 percent in high schools and colleges.

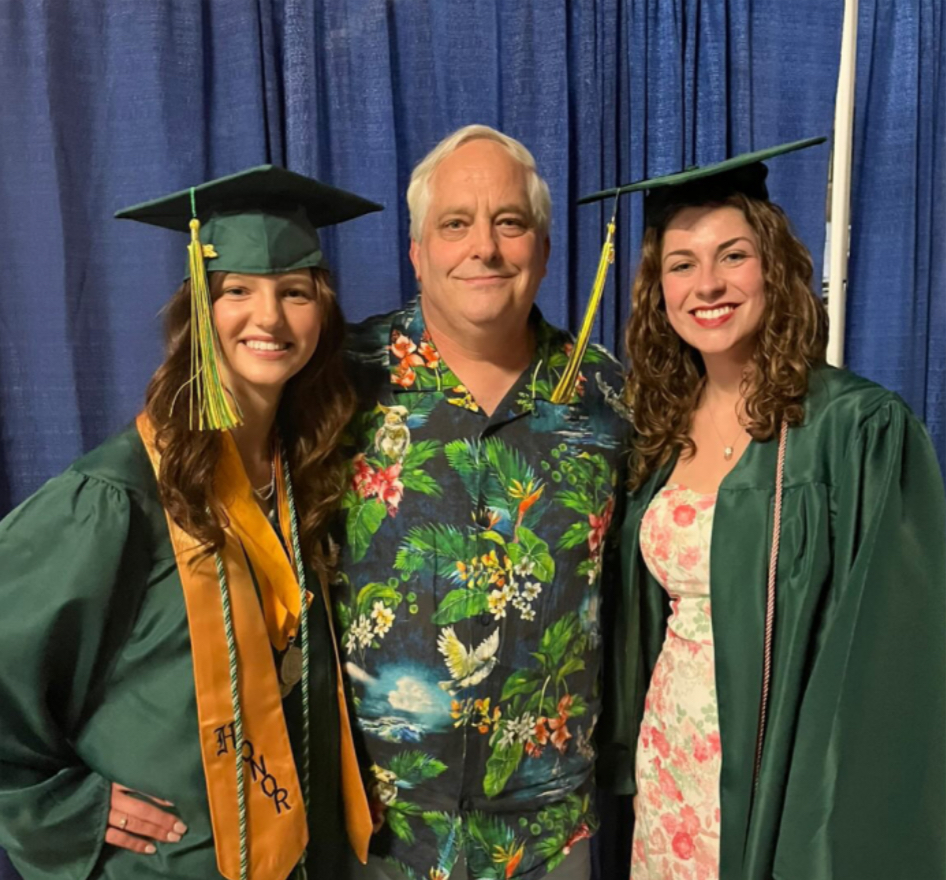

Athletic Director Karen Hanks saw first hand how the law changed her high school.

“There was no girls soccer team my freshman year,” she said.

In 1980, at Ganesha High School in Pomona, the coach of the boys soccer team invited her to come to a team meeting to possibly join their team her junior year. But when she showed up with all of the girls who wanted to play, she was told only she was welcome.

Hanks promptly left with her friends and when her father heard about the incident, he went straight to the principal, who was forced to create a girls soccer team or face a lawsuit, under Title IX.

Women athletes also had few opportunities at Rio.

Debbie Meyer, a Rio Americano graduate, won three Olympic gold medals in Mexico City in 1968 while still a student here, but based on yearbook team photos, there were no women on the swim team that year.

In fact, there were no women sports in the Tesoro until the women’s tennis team appeared in 1973, a year after Title IX was signed into law.

There was intense discrimination women in sports at all levels, Meyer recalled during an interview this week.

“I felt it at the (Olympic) Games,” Meyer said. “We were segregated from the men, having our own place way away from the men. The number of men that could make the team was more than the women. They had more events than us.”

The problem was especially severe at the high school level.

“There were no competitive sports for girls in high school in California when I attended school,” Meyer said. “This is odd as I was inducted into the National High School Hall of Fame.”

Showing the benefit of the law here, earlier this month the Rio women’s swim team and women’s soccer team repeated as Sac-Joaquin section champions.

Not only did these and other sports produce trophies and scholarships, studies show that girls who participate in high school sports are much more likely to go to college, as well as attaining higher-paid job. In fact, girls who play sports in high school or college average 14-19 percent higher wages, according to the Johnson Research Institute survey.

While not necessarily well known now, the law’s effects are still greatly appreciated.

“Womens athletics gives girls the opportunity to compete just as boys do,” senior soccer player Lauren Elledge said. “Sports can be the way into careers and schools which frame the rest of our lives.”

It seems the 40-year-old law has become so successful that teenage female athletes often have no idea what Title IX is.

Senior soccer player Sofia Jimenez was among the many athletes who had not heard of the law. But, as far as athletics go, she said, “I think it’s pretty equal right now.”

The lack of awareness most young people have about the law may indicate its success, however in the words of Bay Area soccer star Brandi Chastain at a Capitol ceremony honoring the law, “It’s important to remind people.”