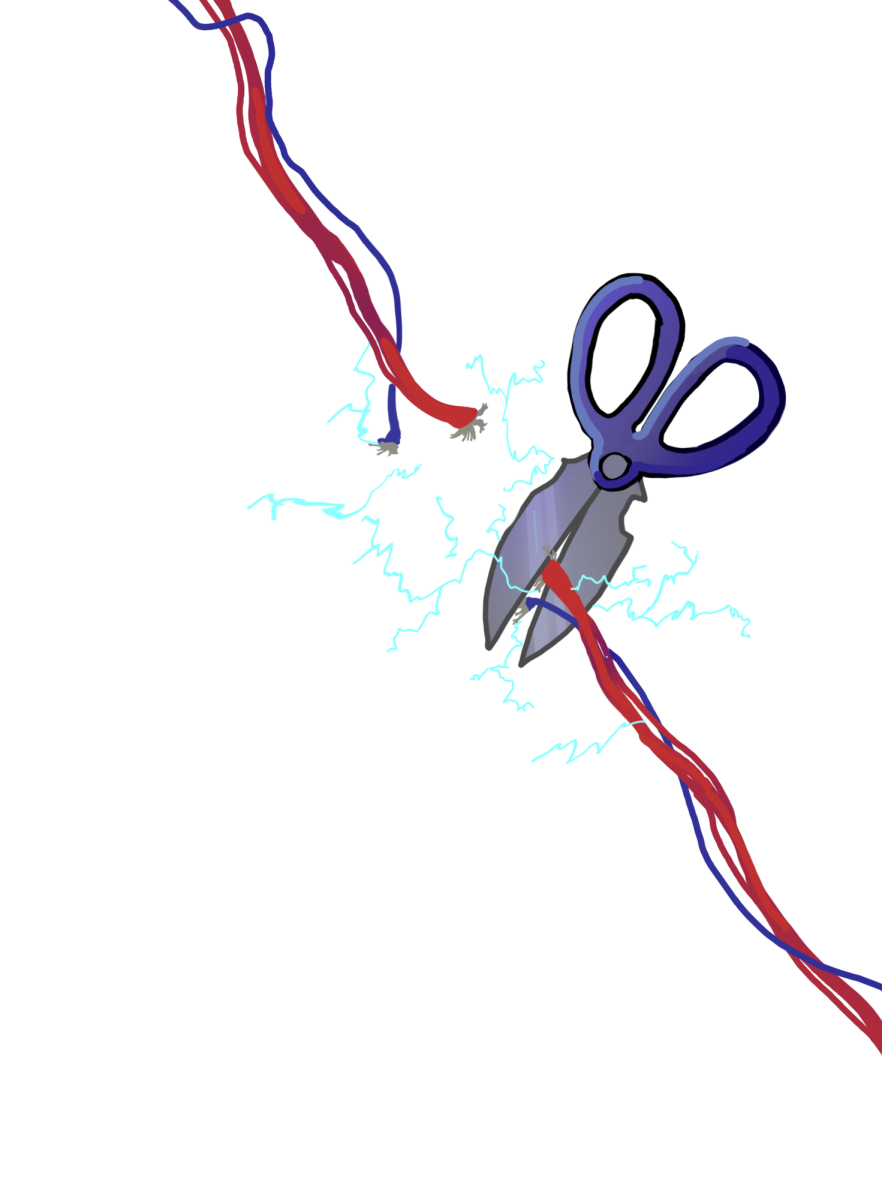

When University of Alabama football coach Nick Saban said that Texas A&M “bought every player on their team,” he started a firestorm. But what was largely ignored in the ensuing controversy was the spark that exploded the powder keg—the NCAA’s decision last year to let players profit off of previously-forbidden name, image, and likeness (NIL) deals, allowing student athletes to earn money from sports, their team, or outside entities. While legalizing these deals initially seemed like forward progress, it has backfired; NIL deals are ruining college football competition.

When University of Alabama football coach Nick Saban said that Texas A&M “bought every player on their team,” he started a firestorm. But what was largely ignored in the ensuing controversy was the spark that exploded the powder keg—the NCAA’s decision last year to let players profit off of previously-forbidden name, image, and likeness (NIL) deals, allowing student athletes to earn money from sports, their team, or outside entities. While legalizing these deals initially seemed like forward progress, it has backfired; NIL deals are ruining college football competition.

The ban on NIL deals ensured fair and free recruiting for all teams, regardless of the size of their booster clubs or budgets. Unlike professional leagues, where players typically go to whichever team will pay them most, college teams couldn’t have bidding wars where the schools with the most money won. While NCAA rules prohibit “NIL compensation contingent upon enrollment,” this is poorly enforced. Boston College standout Zay Flowers received multiple offers from third parties, one of an astounding $600,000, to transfer prior to this season, according to ESPN. Sports Illustrated reported that a University of Utah player was offered almost $1 million to transfer. Players are going to attend where they will profit most, which is the bigger schools. Smaller ones will struggle to recruit in what is often already an uphill battle for them.

Even if the NCAA had better enforcement against this rule, “legal” deals are still problematic. Anyone can make deals with athletes as long as they don’t include a contingency to attend a certain school. Avid University of Miami supporter and billionaire John Ruiz made around $7 million in deals to Miami athletes (for which he has since been investigated by the NCAA), the Miami Herald reported. Following this, Sports Illustrated reporter Ross Dellenger found that “Miami poached from UCLA and West Virginia for a total of four players, all starters.” It is impossible to see how the prospect of bigger NIL deals at Miami did not affect these athletes’ decisions.

“Certainly, the idea of NIL was not to recruit guys from other teams, induce them to come to their schools and pay them money or pay recruits on the front end,” Ohio State Buckeyes coach Ryan Day said. “But that’s what this has become.”

The biggest losers of this are small schools. Groups of donors from particular schools have started to form “collectives,” which exist only to provide NIL deals to players at their school. The University of Tennessee’s collective has done almost $4 million in NIL deals. This has led Greg Schiano, head football coach at Rutgers, to raise concern. His school’s moderate-sized program has raised $400,000 for NIL deals through their collective; a sizable sum, but still only 10% of Tennessee’s fund. This system favors the powerhouse colleges, with more well-funded supporters to give college athletes richer deals. As the gap between the good and bad teams widens, competition will plummet. Gone is the classic game where the underdog team rises up against the powerhouse. Expect to see more dramaless blowout wins for the favorite.

Now, over a year after NIL deals were legalized, something needs to happen to prevent college football from spiraling out of control. The NCAA needs to take charge of the NIL landscape, and create a fair environment for all teams. Administrations across the nation need clear, uniform rules regulating how much they can be involved in players’ deals. A solution, perhaps a salary cap, needs to be presented to prevent recruiting from becoming a booster spending war. All college athletes deserve an even playing field to pursue the sport they love, and, hopefully, profit off it—the right way.