National Survey Reveals a New Gender Gap in Education System

Cole Daly has something in common with many boys at Rio and across the nation:

He has excelled on standardized that measure reading and writing ability. And he has failed English.

“I actually do very well in English, but I am very forgetful,” said Daly. “Essays I turn in are usually in the A range, but I don’t do my assignments.”

While Daly takes responsibility for his grades, he is also part of a larger gender disparity in education. National studies and local data reveal that, on average, Daly’s female counterpart will score better on her classwork but worse on her standardized tests.

Talks of gender gaps in the past have been concerned primarily with bias faced by girls in classrooms, or with increasing female involvement in the STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) fields. Now, though, issues surrounding classroom performance are not isolated to one sex.

The data, including studies from Columbia University, The University of Georgia, and grade and test statistics from Rio, suggest that either girls and boys are held to different standards, or the modern classroom dynamic is better suited to girls than boys.

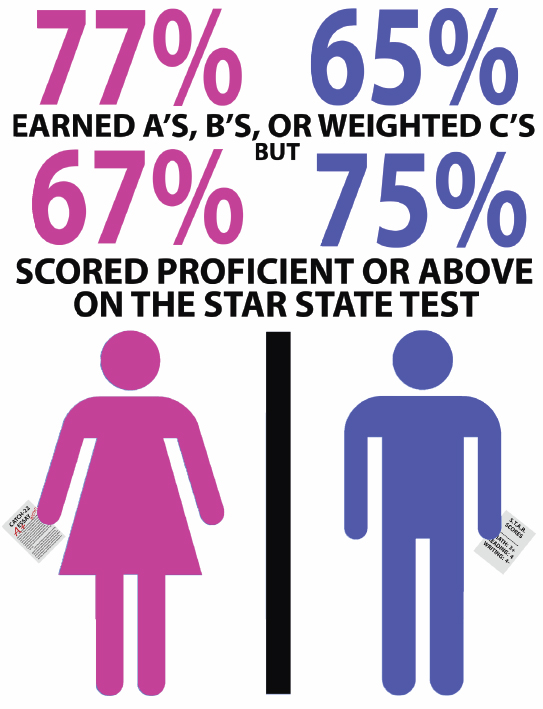

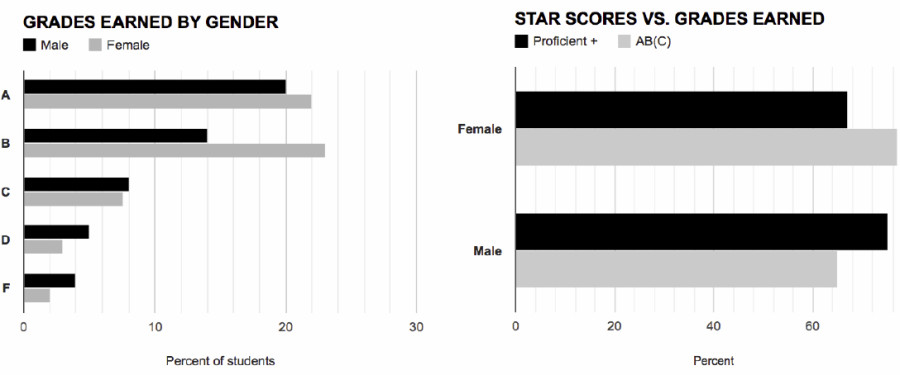

For example, on last year’s junior-year STAR tests for history at Rio, 75 percent of the school’s boys tested “proficient” or above, while only 67 percent of girls earned the same scores.

However, according to school statistics for junior-year U.S. history grades, 45 percent of girls at Rio are got As and Bs and weighted C’s (in AP U.S. History) while only 34 percent of boys are earned the same grades.

The gender disparity is also evident in enrollment in high level classes. Although boys make up 52 percent of Rio’s student population, they account for only 43 percent of students in honors and AP classes. At the other end of the spectrum boys account for more than twice as many F’s as girls in all classes.

Vice Principal Tanya Brown said the discrepancy between grades and test scores raises uncomfortable questions for the school and district.

When faced with a STAR test that does not elicit a huge effort, the scoring level should not vary by much from gender to gender if both learned the same material at the same level, she said.

“It’s not like the boys were trying to kill it,” Brown said. “In the context of the test, (boys) did well–much better than their grades would indicate.”

Concern about a gender gap in education is not new. However, education researchers have mainly focused on bias faced by girls, especially in STEM fields. Now, issues surrounding classroom performance are not isolated to one gender.

According to researchers like Richard Whitmire, author of “Why Boys Fail,” modern schools are unequal and prefer girls over boys.

Boys are falling behind girls, Whitmire argues in his book, because kids now are forced to use literacy skills at ever younger grades and boys take longer to develop those skills. The problems carries over into high school, where boys are more likely to be behind in skills and less likely to try to please teachers.

Whitmire suggests student behavior has a strong influence on their overall grades, skewing the distribution of good class grades toward less disruptive students, who are most typically girls.

“That’s true in a lot of subjects; boys test higher than their grades would indicate,” Whitmire said in an email interview with the Mirada. “That can be explained by the fact that girls are better about homework, they are better writers, and they are less likely to annoy their teachers.”

Whitmire’s observations were reflected in interviews with several boys at Rio.

“Girls put more emphasis on keeping track of assignments and studying” and therefore get higher grades, Daly said. “In class though, boys and girls are on the same level”.

Daly is now enrolled in Nina Seibel’s English Credit Recovery class to make up for F’s he has received in previous semesters. The F’s came when he was dealing with personal loss, but he has never had high grades in English, despite scoring Advanced in English/Language Arts on every STAR test he has taken since second grade, including some perfect scores.

His classmate junior Dylan Hicks has also gotten F’s despite Advanced scores on the STAR test.

“I sit down and do it (tests) and do my best. I have a good memory for facts, but not for an assignment to do something,” said Hicks, who acknowledges his grades reflects many incomplete assignments. “Girls are much more determined.”

Missing assignments and lack of focus are just part of the problem for some boys. Boys have been suspended from school 104 times so far this year, compared to 22 suspensions for girls.

Whatever the underlying causes, the gender achievement gap at Rio reflect national trends. According to the study released last year by the University of Georgia and Columbia University, grade bias starts in elementary school. Researcher say their study shows “gender disparities in teacher grades start early and uniformly favor girls.”

“The trajectory at which kids move through school is often influenced by a teacher’s assessment of their performance, their grades’” wrote Christopher Cornwell, head of economics at the University of Georgia’s Terry College of Business, and one of the study’s authors. “This affects their ability to enter into advanced classes and other kinds of academic opportunities, even post-secondary opportunities.”

The trend continues past high school with more women than men attending and graduating from college across the country. By the time they are 27, 32 percent of women had received a bachelor’s degree, compared with only 24 percent of men, according to a report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Boys interviewed for the article did not see direct bias on the part of teachers. Rather, they saw a problem with the system.

“Most of my teachers are very fair with the treatment of boys in girls,” said Daly. “If they were told they did something wrong they were apologetic and changed”

English and Avid teacher Nina Seibel said that “boys are less driven to impress (teachers),” but a system that awards behavior may favor girls.

“Boys don’t apply themselves fully, and they get distracted more easily,” Seibel said. “And yes, there is an institutional bias against boys.”

While this does not justify bad behavior, it does clearly show a difference based in gender.

Vice Principal Chuck Whitaker believes schools need to do more to meet the different style of boys and girls.

“I know that boys learn differently,” Vice Principal Chuck Whitaker said. “If you’ve got a group of boys you might teach them differently. Different motivations, different strategies.”

need help to impress a boy • May 6, 2014 at 4:33 AM

When I initially commented I clicked the “Notify me when new comments are added” checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get four emails with the same comment.

Is there any way you can remove people from that service?

Thank you!