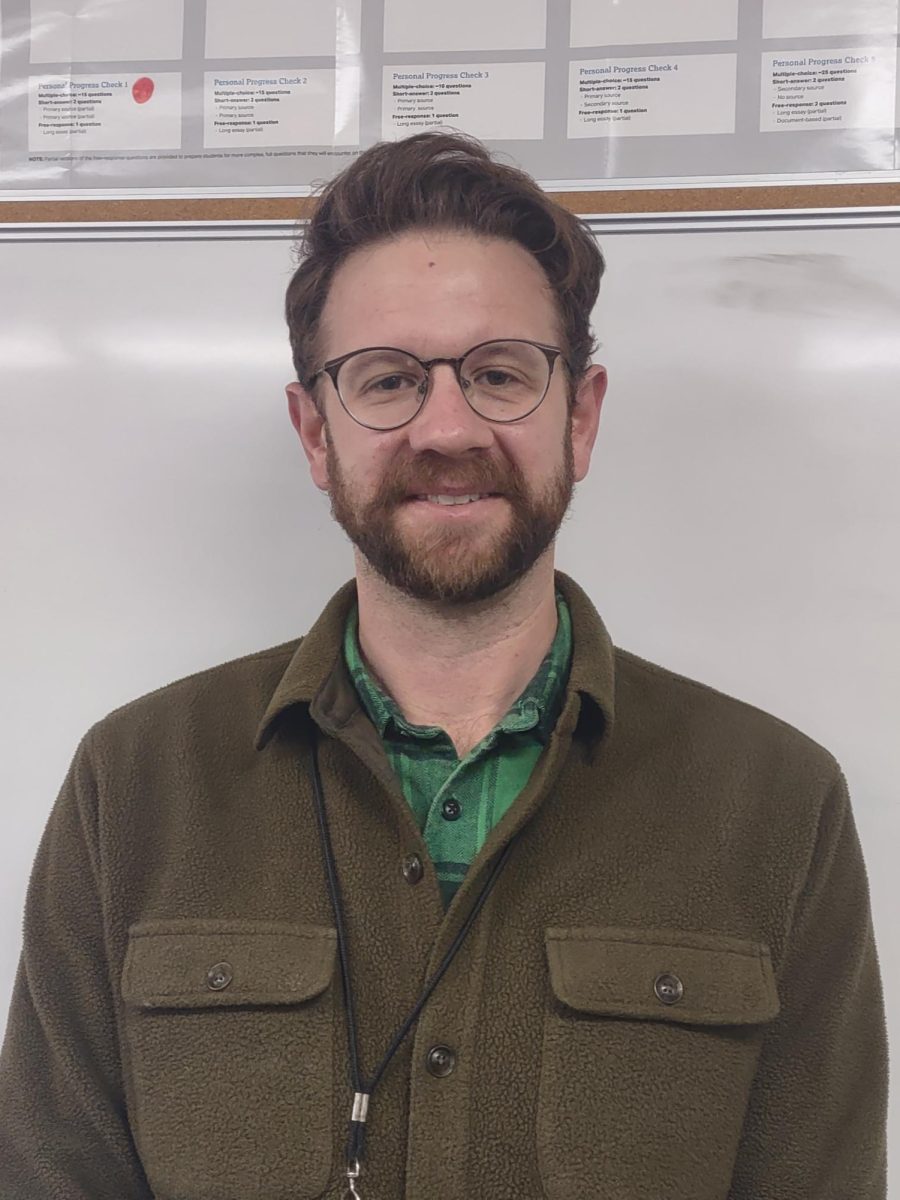

When students enter Adam Bearson’s English classroom, they know what to do: put their phone away immediately. Students begin the semester with 200 free points, but that number is cut in half when they are seen with their phones out.

While many school districts nationwide are taking an aggressive approach to cracking down on student cell phone use, Rio Americano has not opted for an all-out ban. Rather, individual teachers dictate their class policies, with an increase this year in stricter rules and more teachers collecting phones at the start of class.

There is also no San Juan Unified policy restricting all-day cell phone use, only in-class use. According to Rio principal Cliff Kelly, the path taken by the district in the next few months will determine any future rule change at the school level.

But all that will change if a bill passed by the California legislature in late August is signed by gov. Gavin Newsom. The legislation, which would take effect in 2026, requires schools statewide to develop policies banning phones during school hours. In the meantime, districts can implement their own bans.

Rio teachers vary widely on their current cell phone policies. Many teachers require phones to be turned in at the start of each class while others take a more lenient approach.

“[Cell phone use in class] prevents students from having a creative and original thought, and it makes them anxious and sad,” said English teacher Adam Bearson, who requires students’ phones remain in designated baskets during his classes. “It’s distracting to students. It’s not really my opinion, I’m just following the research.”

Bearson said that a school-wide ban should be enacted if 65% of the staff support it.

Kelly said that while in-class bans can be beneficial, a campus-wide ban, which would include lunch and break times, might not be the best course of action.

“If a student is at lunchtime and they’re just talking to their mom or sister or friend or they need to make a phone call to check on their car insurance, I don’t know if the school should necessarily look to be banning that,” Kelly said. “Because at that point what you’re talking about is no cell phones on the campus. That’s a different situation. How are you going to regulate that? Is that going to be supported by parents? Do parents feel that there is now a safety issue?”

And while the safety question can be at least partially addressed by the availability of a landline in every classroom, cell phones do provide convenience and immediacy, Kelly said.

“There was a period of time before I was a principal when I was a teacher and I had a simple rule: I just don’t want to see it,” Kelly said. “So my expectation was students put it in their pocket or put it away in their backpacks. But I also understand that was long ago.”

In June, the Los Angeles Unified School District became the largest district in the country to pass a ban on student phone use. Beginning in January 2025, students will no longer be allowed to spend time on their phones or social media during the school day.

Many schools are testing “phone lockers” or locked pouches that can only be opened by administrators or a special magnet.

While administrators at schools with complete bans say compliance is high, some students try to get around the ban by breaking into their locked pouches or putting dummy phones in the lockers.

Complicating efforts to ban phones is a new state law that went into effect in July that prohibits California schools from suspending students for acts of willful defiance. This means schools have limited options for dealing with students who refuse to turn in their phones or who use a phone during class.

But not all students are on board with the changes.

“I have noticed a change in cell phone policies in specific classrooms,” senior Maya Ayala said. “I think that collecting the phones does help me focus, but then I’m paranoid about where my phone is.”

Social media, she said, is the problem with mental health issues, not phones as a whole.

Some students also say they oppose the use of pouches and phone lockers.

“I think that the idea of making sure phones are put away is smart, although I don’t think that personal property should be collected at the beginning of class without reason,” senior Sadie Burns said.

Every student the Mirada spoke to acknowledged the problems with excessive cell phone use but stopped short of supporting a full ban.

Beyond the distractions cell phones create during class instruction, teachers and lawmakers are increasingly concerned about the negative impacts of phone and social media use on students’ mental health.

It is not uncommon to see students hunched over their phones alone at lunch, breaks and passing periods, a trend cell phone bans seek to change by promoting real interaction.

This summer, U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy called for health warnings on social media for younger users, similar to those found on cigarette packages. He also expressed support for schools to become phone-free environments.

Since 2010, the number of U.S. teens with depression symptoms rose 161% for boys and 145% for girls, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Nearly 30% of girls and more than 10% of boys have “major depression.”

In college students, anxiety rates increased 134% in that time period, depression increased 106% and ADHD jumped 72%, the American College Health Association reports.

At the same time, 95% of teens report they have regular access to a cell phone.

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, author of “The Anxious Generation,” a book published this year that links the “collapse of youth mental health” to increase in time spent on smartphones, wrote that a phone-free environment for the entirety of the school day is the only way to “free up [students’] attention for each other and for their teachers.”