Book bans, challenges increase across country

Rio teacher says objections come from ‘both the left and right’

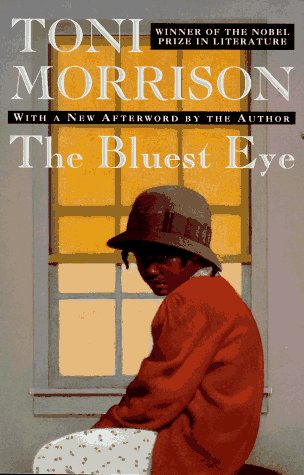

Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” under scrutiny.

An African American girl living in an abusive home, a young girl struggling to solve the disappearance of her best friend, and a young African American individual finding their gender identity while dealing with toxic masculinity. These are the plots of books that are at the center of book banning debates at high schools across the country.

In states such as Utah, Texas, Tennessee, Kansas, North Carolina, and Virginia, parents have protested certain books that they believe are too sexually explicit or that contain uncomfortable storylines regarding race, gender, and sexual identity.

Parents have complained that these books do not foster their children’s learning, but rather just discomfort them. They proposed the removal of books containing “controversial” topics from school libraries and classrooms.

Among the frequent targets are: Toni Morison’s “The Bluest Eye,” Tiffany D. Jackson’s “Monday’s Not Coming,” and George M. Johnson’s “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” a memoir about being a black, queer boy.

The topic of banning books has made its way into politics, and some politicians have responded to the complaints by backing calls for removal, while others are against it. A clear example of a politician in agreement with the removals can be found in Virginia where Republican Glenn Youngkin defeated Democrat Terry McAuliffe in the race for governor in part by backing a parent who did not want their son to read Morrison’s Pulitzer-Prize winning novel “Beloved” in a senior AP English class.

Although most of the challenges against books are not taking place on the West coast, the question of if they could eventually affect students here still remains open. If so, teachers would be limited as to what books they could assign while students would have less options of reading materials.

Librarian Laura Fierro has been following the ongoing attempts to remove books from high schools and takes a measured approach. Though the Rio library contains many of the books that high schools country-wide are challenging, there have only been a handful of efforts to remove them by concerned parents.

“I understand the perspective of a parent of maybe wanting their child not to read or be exposed to certain content whether it may be the school library or a public library; however I think there’s a limit,” said Fierro. “They can say that for their kid but for them to say they want a book banned from the whole library, I think then they’re limiting access to other people.”

Parents have the option to ask for a separate reading assignment for their child if they are not comfortable with a book assigned in English. But similarly to Fierro, many Rio teachers believe the problem lies when people try to make books unavailable for everyone else.

To veteran English teacher Jolynn Mason these attempts to ban books remind her of the book her English 1 Honors class is currently reading. “Fahrenheit 451” by Ray Bradbury depicts a world in which books are outlawed and burned at 451 degrees. Ironically, this novel is often a topic of discussion within groups of parents trying to get rid of certain books from their schools.

“I don’t like the implications of banning books,” said Mason. “I think it hearkens back to authoritarian regimes where they used that to suppress knowledge and freedoms, so I think it’s a dangerous path to go on.”

Video Productions and English teacher Adam Bearson, however, is more disappointed than anything about parents trying to limit what reading material students have access to.

“Now, with woke politics being what it is, people on both the right and left are trying to ban books and it’s just the question of what books to ban,” said Bearson. “I’m a little bit discouraged to see that there’s no longer strong advocates for book freedom.”