On Sept 2, 2020, conservative activist and City Journal contributing editor Chris Rufo appeared on Fox’s Tucker Carlson Tonight to demand action on what he called critical race theory.

“I call on the president to immediately issue this executive order and stamp out this destructive, divisive, pseudo-scientific ideology at its root,” he said.

Two weeks later, President Donald Trump announced in a White House news conference on American History his plan to sign an executive order to establish the 1776 Commission in order to “promote patriotic education” and grant the National Endowment for the Humanities support to develop a “pro-American curriculum that celebrates the truth about our nation’s great history.”

Rufo, it was observed, had the president’s ear.

In the past year, critical race theory has gone from an obscure academic approach for studying the role of race in society to one of the most hotly debated education topics in the country.

Critical Race Theory

Although few people had heard of CRT a year ago, by last spring it had begun fueling impassioned demonstrations at school board meetings, and as it turned into a hot-button political issue more than 20 states proposed or passed laws restricting what schools could teach about race relations and American history.

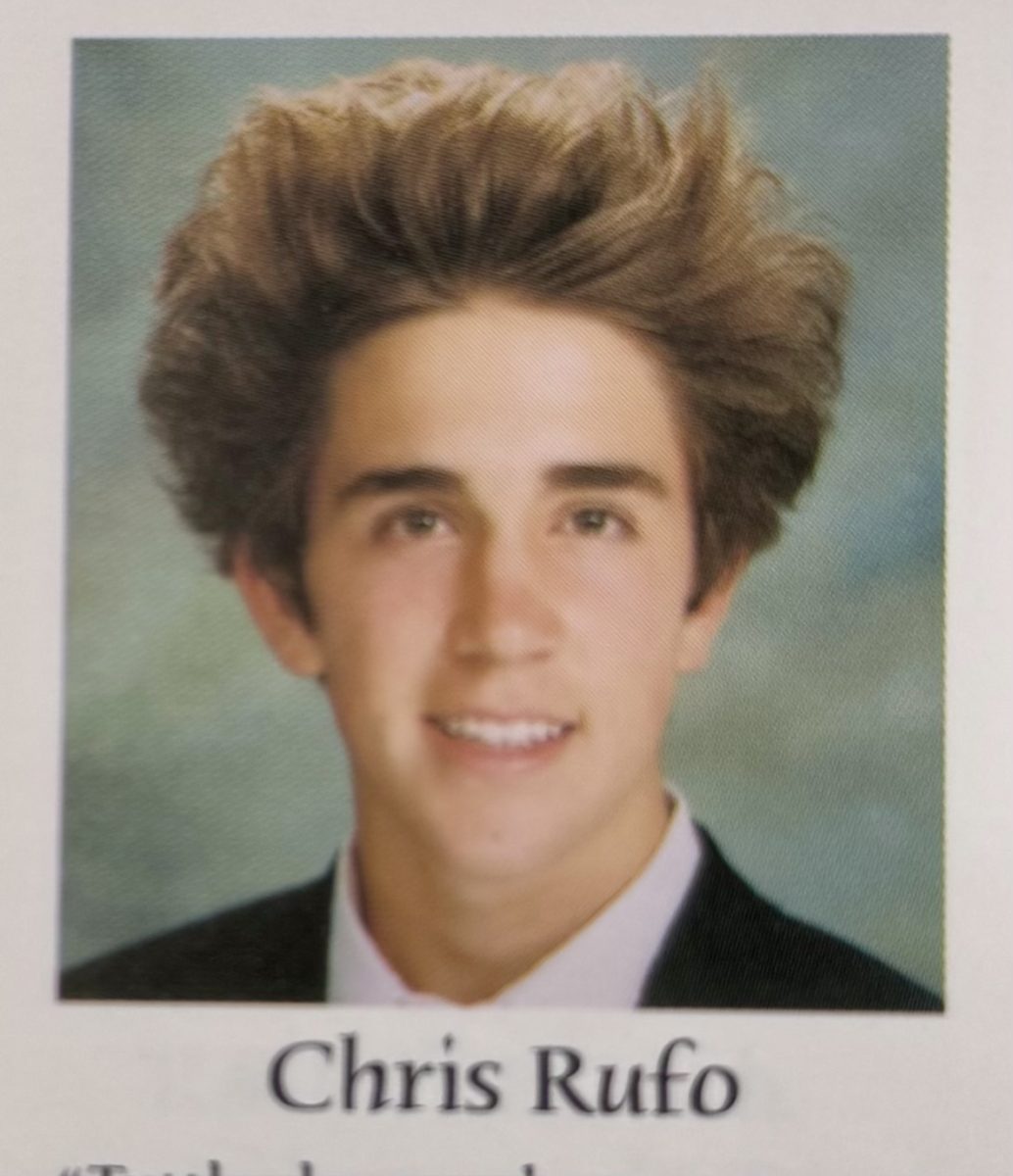

As ubiquitous and controversial as the topic has become, CRT may never have entered the public consciousness if not for one conservative activist calling out what he sees as extreme practices of racial indoctrination and unfair criticism of America. That activist, who has gained the attention of Fox News hosts, Republican politicians and former President Trump is Christopher Rufo, a 2002 graduate of Rio Americano High School.

In an email interview with the Mirada, Rufo described critical race theory as “an academic discipline that holds that the United States is a nation founded on white supremacy and oppression, and that these forces are still at the root of our society.”

Although critical race theory has a complicated history and a broad, often disputed set of ideas, UC Berkeley School of Law professor Khiara Bridges identifies four key tenets of the framework: recognition of race as a social construction rather than a biological entity, acknowledgment that racism is embedded in institutions and systems of our society, rejection of the popular consensus that racism exists only in stand-alone incidents, and the value of the lived experiences of people of color in scholarship.

Critical race theory first emerged in the late 1970s and early 1980s among a group of Harvard Law students and professor Derrick Bell who protested a lack of diversity in their school’s curriculum. Student Kimberlé Crenshaw organized the first Workshop on Critical Race Theory in 1989 at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. It was not until 1995 that critical race theory was applied to the field of education, when pedagogical theorists Gloria Ladson-Billings and William F. Tate used it to better understand inequalities in schooling.

Now, as the issue has become a widespread controversy dividing parents and educators across the country, we are faced with the question of how schools should be teaching about race and racism.

At Rio

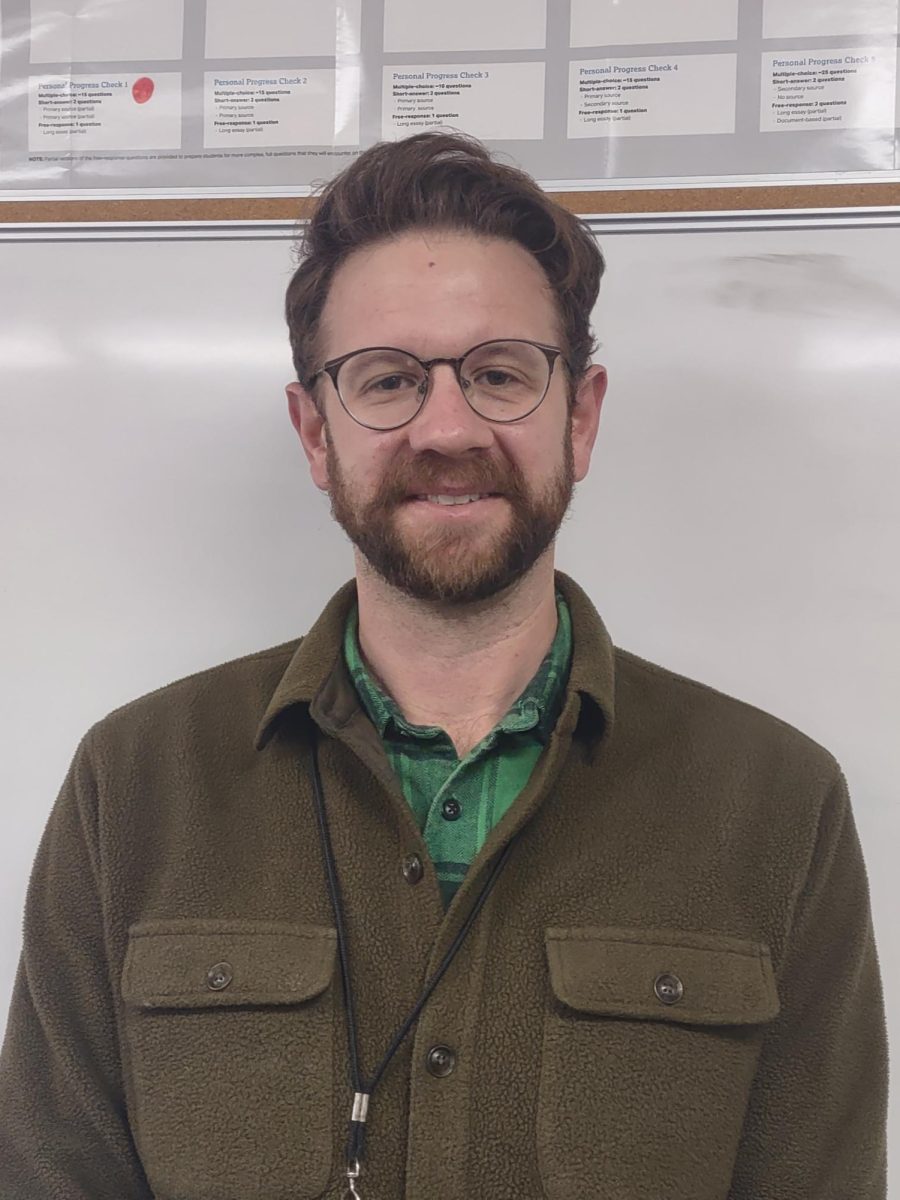

Rufo has indicated that was the sort of high school education that he received at Rio.

On an episode of the New York Times podcast, “The Argument,” he mentioned that in his history class he learned about facets of racism including slavery, segregation, Jim Crow, Native American genocide, and Black Codes. His fellow guest, Stanford Law professor Ralph Richard Banks, remarked that he must have had an “extraordinary education,” as he encounters law students in his class who are shocked to learn about the extent of some of these practices.

Banks argues that schools should teach in a way that recognizes the centrality of race in American history, without making students feel bad about their identities.

When asked by the Mirada to expand on his education at Rio, Rufo responded succinctly, “ Mr. (Richard) Thorn was an excellent AP history teacher.”

Thorn could not be reached for this article, but another of Ruso’s former teachers, who asked not to be named, described Rufo as smart and a sort of a “brat” who was full of opinions. Rufo was not the hardest-working student, the teacher said, but he aced all his tests.

An outgoing student, Rufo is immediately recognizable in yearbook photos by his teased-out mop of light brown hair. Deeply involved in the school’s much-lauded music program, as a senior he was in the honors concert band and played guitar in the top group, AM Jazz.

Rufo’s father was born in Italy, and Rufo’s senior quote in the Rio Americano yearbook in Italian translates to “All roads lead to Rome.”

Road to Success on the Right

After high school, all roads for Rufo pointed to his current status as a rising conservative star. He graduated from Georgetown University’s Walsh School of Foreign Service in 2006. But in 2008 he quit his job to travel to Mongolia with his friend and fellow filmmaker Keith Ochwat to make the well-reviewed PBS documentary “Roughing It: Mongolia.” The two later taught a documentary film school in Sacramento that was attended by several Rio students.

A conservative since his high school days, Rufo’s view on race and poverty moved further to the right while he was directing “America Lost,” a 2019 documentary about struggling cities, including Stockton.

He had championed several conservative causes–including joining a successful lawsuit to block Seattle’s proposed income tax on individuals making over $250,000 a year and publishing a paper criticizing the city’s homeless policy as driven by “socialist intellectuals”–but he shot to national prominence with his attacks on what he called critical race theory in public institutions.

While Rufo is passionate about ending things like diversity training and race-centered history curriculum, he also says that criticizing CRT is a weapon to be used against the left.

In March of 2020 he wrote on Twitter that his aim was to lump many liberal programs under CRT, gaining opponents to these programs by association.

“We have successfully frozen their brand—’critical race theory’—into the public conversation and are steadily driving up negative perceptions,” Rufo wrote. “We will eventually turn it toxic, as we put all of the various cultural insanities under that brand category. The goal is to have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think ‘critical race theory.’ We have decodified the term and will recodify it to annex the entire range of cultural constructions that are unpopular with Americans.”

Whatever his broader purpose, Rufo has sparked heated debates about public education that have divided schools and communities.

While Rio has not seen such a violent rift and meetings of the San Juan USD have not exploded into shouting over curriculum as have meetings across the country, students are still divided on the role of critical race theory in education.

Nikita Rogaski (11) said, “Topics surrounding critical race theory should never be restricted on an educational campus because it would prevent students from learning about historical hardships, halt the strides we have taken to stop racism, and even bolster the discrimination that is already present in many schools.”

However some share Rufo’s concern that critical race theory is too extreme to be applied in classrooms.

“It is important that we address these parts of history in schools because, though it may feel uncomfortable, it teaches awareness,” said junior Brinn Wallin. “That doesn’t mean we must teach it through extremes like the critical race theory, though.”