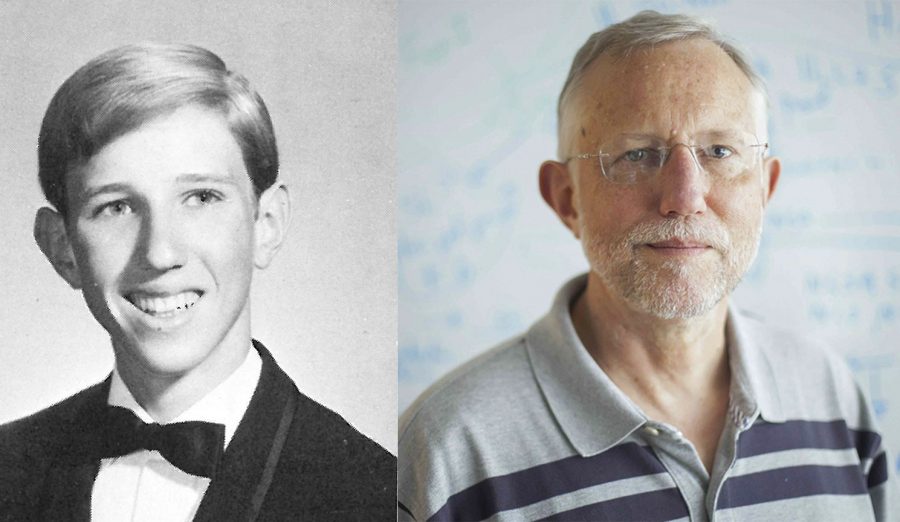

Rio Alum Wins 2020 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine

Rice, a 1970 graduate, made discoveries that led to a cure for Hepatitis C

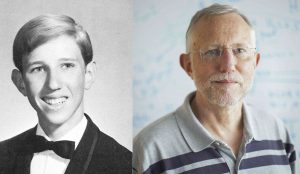

Photo By Michael Mahoney

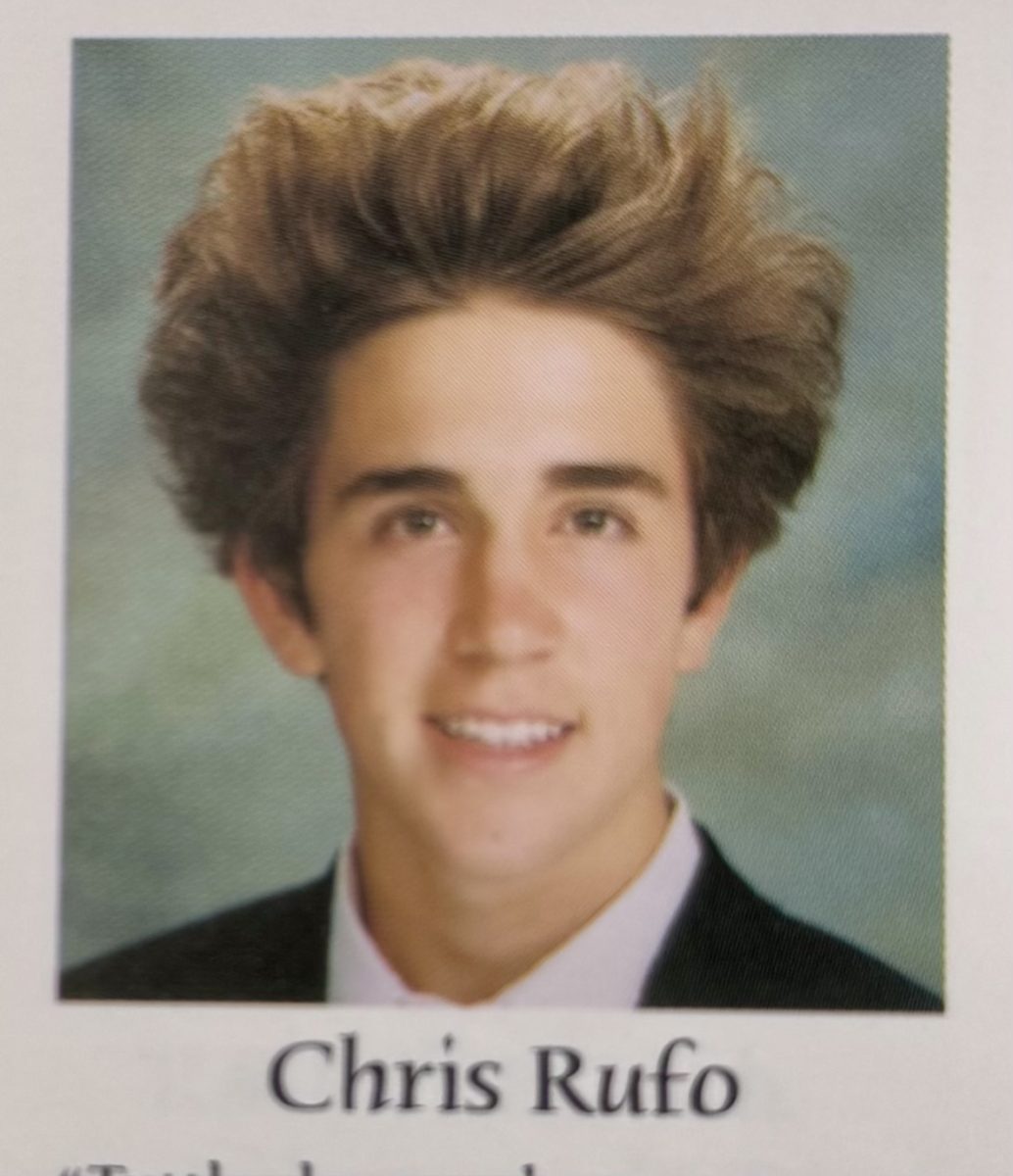

Charles Rice, who won the 2020 Nobel Prize for Medicine, graduated from Rio in 1970. His senior portrait is shown on the left.

Alumnus Charles Rice received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine last week for his groundbreaking contributions to treating Hepatitis C, marking the first Nobel Prize winner to graduate from Rio Americano.

In announcing the award, the Nobel committee noted that Rice and his co-winners Harvey J. Alter and Michael Houghton “made a decisive contribution to the fight against blood-borne hepatitis, a major global health problem that causes cirrhosis and liver cancer in people around the world…The discovery of Hepatitis C virus revealed the cause of the remaining cases of chronic hepatitis and made possible blood tests and new medicines that have saved millions of lives.”

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in zoology from UC Davis, Rice received his Ph.D. in 1981 in biochemistry and performed post-doctoral research at California Institute of Technology, later moving to teach and conduct studies at Washington University in St. Louis. Since 2001, Rice has been a professor of virology at Rockefeller University, where he has led the Center for the Study of Hepatitis C for 17 years.

But before his higher education and contributions to curing Hepatitis C, the Nobel laureate was raised in Arden Park and attended San Juan Unified schools.

The Sacramento Years

After attending Mariemont Elementary School and Arden Middle School, Rice found himself at Rio where he enjoyed a variety of subjects, but was still unsure of what he wanted to do in life.

“In general I thought that the classes were really good,” Rice said in a zoom interview from his office in New York on Monday. “I probably wasn’t the best student in the world, but I enjoyed math and chemistry, but also English, literature and so on.”

Rice spent his high school days taking traditional core curriculum courses and recalls that when he was in high school there were not the plethora of electives offered to young students today.

Rather shy as a teenager, Rice did not participate in multiple clubs or sports in high school, although yearbooks from his time at the school show involvement in Key Club and student government. Away from school, he was fond of the outdoors. While the American River Parkway was not yet the paved bike trail of today, Rice spent time fishing from the river banks and rafting.

After graduating from Rio in 1970, Rice elected to continue his education at UC Davis.

“My trajectory out of Rio was to maybe get away from home, but not too far, hence the 50-mile trek to UC Davis,” Rice said. “I grew up with dogs instead of brothers and sisters, and I thought going to Davis would be good if I had an eventual interest in veterinary medicine.”

Rice’s story is evidence that students do not need to have a certain direction in life before graduating high school–or even college for that matter.

“I started taking introductory classes in math and chemistry, but just kind of drifted around actually for almost my entire time there,” Rice said.

Rice majored in Zoology after dabbling in various courses from Viticulture (the science of winemaking) to Spanish literature, which he added as a minor.

Rice’s innate interest in biology was fueled by professor Dennis Barrett, now at the University of Denver, who would become one of Rice’s mentors throughout his higher education.

“I guess the defining moment for me that set me on this particular trajectory was an introductory biology class that was taught by Dennis Barrett,” Rice said. “He was just a really great teacher. I think he instilled in me a curiosity about biology, which I had anyway.”

Rice went on to participate in some of Barrett’s research on developmental biology, working with sea urchins at UC Davis’s Bodega Marine Laboratory. Barrett provided Rice with many opportunities, including a summer course in physiology at Woods Hole, a renowned oceanographic institution in Massachusetts.

Graduate School and Beyond

The research at Woods Hole further stimulated Rice’s interest in cell biology and zoology, although Rice was still debating career paths.

“I was kind of waffling between doing a PhD and doing research and being a grape grower and a winemaker,” Rice said. “At that point I decided I was just going to take a break, and I had a Spanish literature minor in college, so with some friends from Davis I bought a used Volkswagen bus and headed off into Central and South America for the better part of a year.”

Yet, before heading south, Rice submitted one application to graduate school at California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, the famed research institution with a history of producing Nobel laureates, and the same institution where Barrett first studied sea urchins as a graduate student.

“I was actually in Lima, Peru, and my dad sent me (in those days it wasn’t email) a telegram stating that I got an acceptance letter from CalTech and they wanted to know if I was actually going to go there to graduate school,” Rice said.

Upon this letter, Rice decided to go down the research route, and accepted the offer to attend CalTech. To prepare for his PhD program, Rice left his adventures in South America and returned to Woods Hole as a teaching assistant for the physiology course that had fostered his own enthusiasm for science.

CalTech appealed to Rice because of its well-known sea urchin lab, among other reasons, but upon his arrival, he was placed in a virology lab instead.

“I guess that was initially sort of a surprise or disappointment,” Rice said, but he shared that accepting where life took him and keeping an open mind led him to the niche of biology that led him to his Nobel Prize.

“I ended up in the Strauss lab working on viruses and I really fell in love with doing that kind of research and that sort of set me on the course that I have been on since then,” Rice said. “I have been very lucky to have landed on something by this sort of random drift.”

This opportunity paved the way for Rice’s future research. Rice studied yellow fever at CalTech, which eventually aligned with international scientists’ work on the Hepatitis C virus (HCV).

“Here I was three years into my career as a junior group leader and this very significant human pathogen ends up in the same family of viruses that I had been devoting a lot of attention to,” Rice said. “There was really no escape when you started working on something that causes this level of human disease.”

As of 2016, there were an estimated 2.6 million people living with HCV. Co-laureates of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Medicine, Harvey Alter and Micheal Houghton, identified HCV in 1989, but it wasn’t until 1997 that it was confirmed that the Non-A and Non-B cases of Hepatitis were in fact caused by HCV.

Building off the work of Alter and Houghton, Rice and his team later developed three new types of drugs that, in conjunction, can effectively destroy the virus.

The Nobel committee praised their work in discovering the Hepatitis C virus as a “landmark achievement in the ongoing battle against viral diseases.” Their discovery has nearly eliminated hepatitis from transfusions and led to the development of new antiviral drugs “greatly improving global health” and “raising hopes of eradicating Hepatitis C virus from the world population.”

Advice for aspiring scientists

The 25 years from the identification of HCV to creation of valid treatments was a transformative time, and Rice was grateful to stumble upon such an important project.

The time Rice dedicated to viruses introduced him to many people and organizations he doubts he would have interacted with had he not pursued virology. He had the opportunity to stay in touch with patients from diagnosis, throughout his research, and to the day that they could be cured.

“It’s pretty special,” Rice said. “It doesn’t often happen that you can begin working on something when it’s a mystery virus and then going to a point where we can cure most people.”

Rice is deeply curious about cell processes, and urges high schoolers to find a career they are passionate about. He would want to be studying viruses even if he wasn’t getting paid to do it, a mindset he equates to some of his success.

“This is kind of like a hobby,” Rice reflected. “If you can land on a career path that overlaps with what you would want to be doing anyways, that’s the greatest.”

There will always be bumps in the road, Rice conceded, especially in research where results do not always go as planned, but his love for virology motivated him to stay committed to studying HCV.

“I think the most important thing is to really have curiosity and passion for your career choice,” Rice said.

Navigating college with curiosity and approaching his future with an open mind, Rice discovered a passion that would become his life’s work and save millions of lives.

“You just have to try and do your best at whatever you do, with passion and rigor and respect for your peers and others working in the same area,” Rice advises.

When Rice graduated from Rio Americano, he had not yet pinpointed his passion, but 50 years later, he awaits the formal ceremony in December to receive his Nobel Medal.

Madison Flores • May 22, 2021 at 3:57 PM

People say that in high school you should know what you want to be when you grow up and I used to believe that, but after reading this article I don’t believe that anymore. I used to be scared that I would finish high school and not be successful in life because I didn’t know what I wanted to be, but this article gives me hope and faith that I will be successful. Instead of knowing exactly what he wanted to be when he grew up Mr. Rice followed the path that life lead him down, which is inspiring. Near the end of the article Mr. Rice explains that it’s better to do what you love. “This is kind of like a hobby,” Rice reflected. “If you can land on a career path that overlaps with what you would want to be doing anyways, that’s the greatest.” “I think the most important thing is to really have curiosity and passion for your career choice,” Rice said. “You just have to try and do your best at whatever you do, with passion and rigor and respect for your peers and others working in the same area,” Rice advises. I love these quotes and find them to be very true. I loved reading this article and found it to be very interesting and inspiring. I am proud to say that I go to the same school that Mr. Rice went to during his high school years.

Rachel Keating • Nov 28, 2020 at 5:04 PM

This article gives me hope as a student confused about my aspirations for the future. Rice wasn’t sure either, but he pursued his callings as they came, and didn’t make a living in them if he outgrew those interests. Towards the end of the article, the author quotes Rice when saying, ‘“This is kind of like a hobby,” Rice reflected. “If you can land on a career path that overlaps with what you would want to be doing anyways, that’s the greatest.”’ Living out your unique purpose in life isn’t always going to align with your ideal financial situation, but you’re truly blessed if it does.

Preeda Anukar • Oct 30, 2020 at 10:59 PM

I accidentally came to know that I have contracted Hepatitis B. I actually don’t know how or when I contracted it but I have it, I was so depressed to know about it, but WorldHerbsClinic HBV HERBAL FORMULA was a blessing for me, I am thankful to everyone here. After three months of using their HBV HERBAL FORMULA, my test result came out negative..Please don’t neglect this testimony, because is 100% real. Thanks.

Mia Eiremo • Oct 28, 2020 at 11:33 PM

This article is what teenagers and young adults need to hear. It can be so easy to get caught up in the status that comes along with school. Most of us want to be the smartest, most “popular” or the cool person in school. But it is often based on what others think of us. Rice makes it visible to people all around that grades do not define you. It is better to live in the moment and pursue what you love. Our career should not be based on what other people want for us. We should all do the best we can and fight for what we love.

GraceAnn Lesser • Oct 26, 2020 at 12:58 AM

I was inspired by this article because I have no discernable direction in life. By studying what interests me, hopefully I will figure it out.

Sydney Gerety • Oct 25, 2020 at 10:19 PM

This article helped me out a lot. I’ve been feeling so pressured to figure my life out, but this really showed me that it’s not a big deal to not have everything figured out right away. I have an idea of what I would love to do in the future, and this article also showed me that I should pursue that passion. I loved that Mr. Rice said “If you can land on a career path that overlaps with what you would want to be doing anyways, that’s the greatest.” This is what I’ve been hoping for personally, and this shows me that it could happen.

Isabela Sue • Oct 25, 2020 at 10:10 PM

It is especially interesting how Charles Rice was a zoology major and then went into biochemistry not to mention research and teaching. “Rice’s story is evidence that students do not need to have a certain direction in life before graduating high school–or even college for that matter.” It is nice to know that I don’t have to have my life figured out right now. I can go with the flow and follow my interests and still be successful.

Aminah Davis-Macias • Oct 25, 2020 at 9:08 PM

I think this article shows that going after a career path is a state of mind. It is how much hard work you want to put into it will resonate where the career leads you. It also shows that it is ok to not know exactly what you want to do at the start like Rice. “I started taking introductory classes in math and chemistry, but just kind of drifted around actually for almost my entire time there.”

He kind of eased into it, he joined a class that ended up inspiring him to continue learning in that field and turning it into a wonderful career. This article also reveals how going after a career path is a learning process and you will learn something every step of the way which will benefit and assist you in the long run of your chosen career path.

Mika Edwards • Oct 25, 2020 at 9:03 PM

Rice’s story is extremely inspiring to me because as a Rio Americano student, it’s nice to hear about someone so successful that started off at the same place that I’m at. It really hit me when Rice said “I think the most important thing is to really have curiosity and passion for your career choice,“ because I can really understand how having a love for your job can take you much farther in your career than if you didn’t love it.

David Bogle • Oct 25, 2020 at 8:25 PM

This story goes to show that it is more useful to have knowledge in a wide assortments of subjects, so one is able to work on something that they are passionate about when the opportunity arises. This story also shows that for someone to become successful, they do not necessarily need to be extremely successful in high school. What matters is finding something worth investing time in and working on that.

Amanda Sheldon • Oct 25, 2020 at 8:21 PM

The life story about Charles Rice is nothing but inspiring. Throughout high school I have put in my best efforts into my classes and everything that has come my way. However, I have still yet to make up my mind as to what I want to do in my future. It frightens me once in awhile as I am nearing the end of high school with not a clear vision of myself after I graduate. I want to go to college, but I have no idea what I want to major in or what path I want to take after my school years. This article helped me realize that as long as you do not give up and try in everything you do, it will pay off, even if you are not in the position with an end goal. Throughout high school, Rice was unsure of what he wanted to do in life, letting the wind take him. Even after he graduated, he was indecisive and moved around different studies, “The research at Woods Hole further stimulated Rice’s interest in cell biology and zoology, although Rice was still debating career paths.” In the end, Charles Rice became unbelievably successful, and even received a Nobel Prize. This article is very inspiring to growing students. It proves that if you follow your heart and try your best, you will find your path.

Michala Rapozo • Oct 25, 2020 at 8:15 PM

This story is very inspiring to me because it helps show me that I don’t need to be super worried about my future. This story is also particularly inspiring to me and most likely others because he grew up here and in the same neighborhoods as most of us students at Rio. Knowing that someone from our town can do it makes me so much more confident.

Natalia L • Oct 25, 2020 at 7:58 PM

This article inspires me because it proves how you do not need to know what you want to do in life at a young age. I still don’t know what I want to do in the future but this gives me hope. I think it is crazy how much he accomplished, especially since he used to go to our school.

Maribel Arenas • Oct 25, 2020 at 7:15 PM

I think this article is really inspiring and makes me feel confident about how it’s ok not to know what you want to do in the future. I liked how he had many experiences before he settled down with one subject. It inspired me to take chances and find what I truly want to do in the future.

Molly Knepshield • Oct 25, 2020 at 7:08 PM

Charles Rice’s story brings hope to many younger people out there. Countless of high school students are unsure of what they want to do with their lives, and are constantly worried that they are running out of time. However, this article, as well as Charle’s story in general, sheds a little light on the situation and helps these people realize that it is okay to be undecided.

Valeria Vera • Oct 25, 2020 at 5:54 PM

I think everyone can relate to this article in one way or another. Charles Rice struggled to choose what he wanted to do in the future and it took him a long time to figure out what he wanted. Many students go through that exact same thing and despite Charles not knowing what he wanted right after high school he eventually figured it out as life went on and became successful. And at the end of the day, the most important part is that he chose a career which he enjoyed, “This is kind of like a hobby” said Rice

Alyssa Newberry • Oct 25, 2020 at 5:42 PM

I find it very interesting and almost makes me proud to be attending a school with a Nobel Prize winning alumni! In the article, it talks about how you don’t need to know what you’re gonna do in life so early on. You have time to think about it, and you shouldn’t become stressed if you don’t know right away. I have a lot of friends who don’t know what they wanna do once they graduate and this article reassures many that are also feeling this way! My favorite part of the whole article is when he says, “ I probably wasn’t the best student in the world”. It shows many that if you have passion towards a subject, you can accomplish great achievements if you put in hard work and effort, even if you weren’t the best student.

Ethan Huggins • Oct 25, 2020 at 3:53 PM

The story of Mr. Rice’s is very inspiring. Not only was he unsure of what he would do after and during high school, but once he found his passion, he stuck with it until the end. Rice earned one of the worlds most recognizable medals, and he did so with determination and spirit. As Mr. Rice said, “I think the most important thing is to really have curiosity and passion for your career choice.” Mr. Rice inspires people like me with his show of determination and grit to persevere for his goals. To help research on a deadly disease.

Mikael Eury • Oct 25, 2020 at 3:35 PM

In life you do not need to focus on your career from the beginning. The important thing is just to continue on learning no matter what it is. In the end you will find something you enjoy and those subjects that you learned because you did not know what else to do may lead you to something you want to do. As Rice said “I probably wasn’t the best student in the world, but I enjoyed math and chemistry, but also English, literature and so on.” He continued to learn subjects that he enjoyed a little but not something that he wanted to pursue. However this led him to discover something that he really did enjoy and led him to gaining the nobel prize. So even if you feel unsure about your future just continue forward and learn until you find something you will enjoy.

Sam Thompson • Oct 25, 2020 at 2:55 PM

Charles Rice’s story shows that you do not have to have your career path set in stone at an early age, Rice’s story shows that you can take your time and learn about new things and gain new interests before you choose a career path.

Jae Yeon Lee • Oct 25, 2020 at 12:56 PM

Nobel Prize winner, Charlies Rice is an inspiring person who we should set as a role model. He shows that we can do anything we want to by simply setting our mind to it.

Zachary carson • Oct 25, 2020 at 11:51 AM

the article shows that throughout high school you may feel lost, or that you don not really know yet what you want to do and that is ok because you just may bounce between different things before you really find what you want to do. “I started taking introductory classes in math and chemistry, but just kind of drifted around actually for almost my entire time there” this story of Mr. Rice is some what inspirational because i am not exactly sure what i want to do and having a little reassurance in the sense that everything will be on it comforting.

Taylor White • Oct 25, 2020 at 8:58 AM

Charles Rice is the perfect example of finding his passion in the most indirect way and succeeding greatly. I was glad that I read this article which was beautifully written. I was mainly happy to have found out that he hadn’t discovered what he actually wanted to do until he was already at college. A quote from Rice that really stuck with me was, “If you can land on a career path that overlaps with what you would want to be doing anyways, that’s the greatest.” I found this quote to be inspirational because it helps me realize that I don’t have to know exactly what I’m going to do before college and I can still succeed.

Hannah Lee • Oct 25, 2020 at 1:52 AM

It is quite refreshing and is very much necessary for most students and myself, to read about Charles Rice’s experience. There will be that point in time, where patience and experimenting with different subjects will result in peace within chaotic times. Which Rice helps us understand. In fact, you do not need to be this amazing student with multitudes of abilities to succeed in life. No matter where you are in life, you will pull through as he did himself. “Rather shy as a teenager, Rice did not participate in multiple clubs or sports in high school”. I completely relate to Rice as well as how I commend him for being able to achieve so much without these sports and clubs people praise. Overall this was very much inspirational and an important reminder for students today.

Madison Flores • Oct 25, 2020 at 1:07 AM

This article was really interesting to read and it made me realize that you don’t need to know what you want your career to be after high school, or even after college. “I started taking introductory classes in math and chemistry, but just kind of drifted around actually for almost my entire time there.” Rices story inspires me to find a career that I am passionate about, even if I haven’t found one after graduating high school, or college. I’ve always thought, and have once been told, that you should know what you’re going to be and where you’re going to go and what you’re going to do after high school, but Rice has proven me very wrong. His story has also taught me that life is full of surprises and that the key to finding what you love and are passionate about is to just let life take it’s course. Overall, it was very interesting, inspirational, stimulating, and fascinating to read about his childhood and to learn about how he came across the career path that he is passionate about today.

Alexander Troutt • Oct 24, 2020 at 10:55 PM

Reading this article really made me understand that I don’t need to know exactly what is gonna happen for the rest of my life as soon as I graduate. I’m really glad because I’m not completely sure of what I’m going to do right after high school so knowing that a person just like me in my same situation got to such a high achievement really gives me hope for the rest of my life. I’m also just really proud of Dr. Charles because his story is really sweet and just because I’m glad I get hope from this doesn’t mean he shouldn’t be proud of his own achievement and he should celebrate.

Clarissa Minton • Oct 24, 2020 at 3:08 PM

This gives me hope that even if I don’t know what I want to specifically do with my life, there’s something out there for me. I found it interesting how he said that by letting life lead him, he was able to get where he is today. It wasn’t something that he was aspiring to do, but more of something that he was meant to do.

Ajeeth Iyer • Oct 24, 2020 at 2:32 PM

What an honor it must be to achieve one of the most prestigious awards in the world! Firstly, I have to extend my congratulations to Mr. Rice for inspiring those of a younger generation to work hard and follow their dreams. In addition to the inspiration that Mr. Rice provides the new generation high school and college students, the article highlights that you don’t have to decide your career path early on. You just have to follow your passions, and life will direct you to achieving the greatest reward a person can get: pure happiness. Mr. Rice conveys the message that by following his interests and “going with the flow,” he was not only able to attain a Nobel Prize but also the truest form of happiness. Mr. Rice’s happiness is displayed when the article mentions that “he would want to be studying viruses even if he wasn’t getting paid to do it” (Newton). These motivating words encourage aspiring scientists, but they also bring relief to students who don’t necessarily know what career they want to pursue. The article presents Mr. Rice as proof that people can be successful just by following their dreams and hopes, a message that should inspire all.

Zane • Oct 24, 2020 at 1:33 PM

Rice’s story is fascinating, and as someone who has no idea what to focus on career-wise, rather inspiring. As the article puts best, “Rice’s story is evidence that students do not need to have a certain direction in life before graduating high school–or even college for that matter.”

Evie Hofioni • Oct 24, 2020 at 12:15 PM

This article was very inspiring and incredible to think about. I personally do not have a vivid visual when it comes to what I want to do with my future and this article just opens my eyes to the possibilities when you chase a dream. I enjoyed reading this article and I find it crazy that he attended the same high school that my classmates and I go to now. We view it as our school where we have so much work and need to get it done for college. Rice looks at Rio as the place where it all started for him.

Ruth-Mary • Oct 23, 2020 at 1:38 PM

I think that Mr. Rice’s story is inspiring, in the sense that find comfort in the fact that I don’t need to know what I want in life when I’m twenty years old, and I can wait to see where life takes me.

Natalie Brauner • Oct 23, 2020 at 7:54 AM

Rice’s story is inspiring by following your dreams. He didn’t know what he wanted to do in life and he eventually found it. It’s also inspiring by finding ways to help destroy HCV. It is crazy to think that he went here To Rio Americano High School, and the fact he almost did not have this career, he did say, “I was kind of waffling between doing a Ph.D. and doing research and being a grape grower and a winemaker”.

Harrison • Oct 22, 2020 at 9:18 PM

I think it’s rather inspiring how someone who attended the same school I go to today, has been able to bring the world a new light and win such a prestigious award. Just like Rice and many of my classmates, we’re still unsure of what way we want out futures to go. He shows that no matter your talents, you’re still able to accomplish great things for this world. One thing that I like about Rice, himself, is that he was “rather shy as a teenager, Rice did not participate in multiple clubs or sports in high school.” Although this may seem unimportant, I feel as if this could relate to me quite a lot as I haven’t participated all to much in either groups or sports or clubs, which I find rather inspiring due to the fact that someone like me, no matter the qualities, can achieve such wonderful things.

Zenith Rodriguez • Oct 22, 2020 at 9:06 PM

I loved how the article talks about finding a career path which is something that everyone goes through. It shows that you don’t have to know what you want to do for a living yet, it can come at any moment of your life. As of right now, I plan on becoming a dentist, but who knows, five years from now I could want to be a vet. Life is full of surprises and opportunities. “I think the most important thing is to really have curiosity and passion for your career choice,” Rice said, and I fully agree!

Ryan Witte • Oct 22, 2020 at 7:07 PM

Rice’s story is encouraging in that it shows you don’t need to know what you want to do when you leave high school. Rice’s classes had little rhyme or reason yet they were all things that he enjoyed. He showed us that as long as you have an open mind you could stumble across amazing things. Even so it is pretty unlikely of the same thing happening for everyone and even Rice admits that he was, “very lucky to have landed on something by this sort of random drift.” Rice showed that all it takes is an open mind, hard work, and some luck to find the job that you will love.

Nate Schallmo • Oct 22, 2020 at 4:05 PM

It is crazy to think that a doctor that got a Nobel Prize was one letter away from making wine and exploring South America. It just goes to show that the littlest things, such as an acceptance letter, can drastically shift a life for forever. His passion for learning is one that I think we should all take. This man knows so much, yet is humble in the fact that he accepts that his life could be completely different.

Amelia Servin • Oct 21, 2020 at 10:00 PM

Charles Rice’s passionate story really showed that as long as you have motivation, it’s okay to not have your career path all figured out. A lot of people spend lots of time stressing over this and think that they have to plan their whole life around reaching that goal. But his story shares that you don’t have to do that, and instead, you should focus on finding a career that you actually find yourself enjoying for the rest of your life. He states that he enjoys his job and doesn’t find it as a burden, “This is kind of like a hobby,” Rice reflected. “If you can land on a career path that overlaps with what you would want to be doing anyway, that’s the greatest.” I found it very interesting to learn about this new perspective since the normal is always already knowing what you want to be in life. This approach was definitely more reassuring I’m sure to the people who aren’t too sure on their future yet.

Angie Stevens • Oct 21, 2020 at 8:04 PM

Charles Rice is a prime example that one can never predict what their future will hold, but an open-mind and determined attitude can get you very far. As I read this article, I was fascinated by Rice’s work and his studies that have gotten him to where he is today, but I think the most important thing I took out of this, is the importance of never underestimating yourself. The key is to go through life keeping imaginative and determined attitude towards learning as long as possible, and great things will follow. As Katelyn said , “Navigating college with curiosity and approaching his future with an open mind, Rice discovered a passion that would become his life’s work and save millions of lives.” Overall, I think it was inspirational and refreshing to read about Charles Rice’s Nobel Prize win, and learn about his childhood growing up, at the very same place I go to right now.

Nora Smith • Oct 21, 2020 at 4:41 PM

I really admire Rice’s story and how passionate he is about what he does. When speaking on his career he said, “This is kind of like a hobby”. I think it’s really important to enjoy what you do so it’s wonderful that he’s been able to do that. I found it really interesting and even a little inspiring how he really didn’t have a clue about what he wanted to do when he was in high school and how he was just an average student. I feel like I’d usually associate someone who’s been able to achieve such success like Rice as someone who had a vision for their life or like an overarching goal on what they want to achieve but that was obviously not the case with Rice. It was sort of refreshing to read a story of someone who had really no idea about what they wanted to pursue in life but was able to end up so successful.

Guinevere Flanagan • Oct 21, 2020 at 2:27 PM

Reading this article was really interesting and almost stress relieving. It’s crazy that a student at Rio where I go to school won the nobel prize. Charles story shows that you don’t have to know what you wanna do when your in highschool. As long as you take the right path. Even in college he had some idea and knew what he found interests in but wasn’t sure of his final career path. It takes time to know what your future will look like, but if you make good decisions you can do something that your good at and love.

Sumaya Albadani • Oct 21, 2020 at 12:52 PM

Reading this article gave me a sense of comfort that I don’t need to know exactly where my life is going. This made me realize that as long as I’m pursuing what makes me happy that’s all that matters. When Rice says “If you can land on a career path that overlaps with what you would want to be doing anyways, that’s the greatest” it showed me that the most important thing is to find what you love and go from there.

Grace Szejda • Oct 20, 2020 at 9:59 PM

Charles Rice’s story reassured me that it is okay to not have your entire life planned out at 18. When she said, ” Rice’s story is evidence that students do not need to have a certain direction in life before graduating high school–or even college for that matter” it established a sense of peace with knowing that it is okay to be unsure. His outcomes were extradorinary, but helps me and other students realize time will tell what the future holds.

Lilah Cruz • Oct 20, 2020 at 8:48 PM

Finding a career path may take a while for many students fresh out of high school. It took Charles Rice quite a few years to get to where he is now. Rice mentions to Newton, “accepting where life took him and keeping an open mind…” An amazing statement that reassures students that don’t know what to do or where to go after high school. It takes time to have a career path set in stone, sometimes you just have to go with the flow of life and it may take you into a path you will be successful in.

Nikhil Patel • Oct 20, 2020 at 7:48 PM

This article really interested me because, as someone who does not know what they plan on doing in the future, it gave me hope that even if I don’t have a solid career plan, I can still have a very meaningful and successful life like Rice. Rice says, “This is kind of like a hobby. If you can land on a career path that overlaps with what you would want to be doing anyways, that’s great!” I find this to be really insightful advice, and it makes me realize that I should do what I’m passionate about in the future, whether that changes along the way or not.

Jolie Barnard • Oct 20, 2020 at 1:03 PM

I thought his story was really inspiring because it showed you don’t have to have your whole life planned out by the time you graduate high school. He ended up doing really great things despite not initially thinking it was the path he was going to go down.

Darya Pahlavan • Oct 20, 2020 at 5:04 AM

I enjoyed this article because it shows that anyone can achieve greatness. You don’t have to be a genius in high school to do great things in life. I found it interesting that he said, “I probably wasn’t the best student in the world.” I have always assumed that you have to be a great student from the beginning, but now I know it all depends on what your passion is.

Marina • Oct 19, 2020 at 5:06 PM

Very interesting story of an inspiring individual.

Keshav Sreedharan • Oct 19, 2020 at 4:09 PM

It was interesting that despite his early indecisiveness in school, Charlies Rice was still not sure about what he wanted to do while in college. I realized that college itself will not spark something in a student but the experience and the right teachers can as it did with Rice.

Alex Bornino • Oct 19, 2020 at 1:01 PM

This made me think about how a career path doesn’t have to be finalized early on! Newton states, “Accepting where life took him and keeping an open mind led him to the niche of biology that led him to his Nobel Prize.” Crediting his open mind so such an honorable achievement led me to think about my own future and how it does not have to be exactly how I expect. When Rice says your job should be one of your hobbies or what you’d want to do without pay, I took that as very helpful advice. What a great piece!

Abby • Oct 19, 2020 at 11:42 AM

It makes me proud to be at a school that has a prestigious award winning alumni. I also relate to Mr. Rice, in the sense that I am not totally sure what route I want to take, in terms of college and graduate schooling. It can be really hard to know what life path you want to take and there can be a lot of pressure on us high schoolers to have an idea, and pick a path. It reassures me and probably many others that you can be unsure in high school, and even college, feel your classes in college and still become successful. I appreciate that he shared his story with Rio. I think his contributions in the science field are astounding and should be honored as he was with the nobel prize. His story gives reassurance to me about having time to find what I truly love and want to pursue as a career.

Aaliyah Silva • Oct 19, 2020 at 11:37 AM

His story shows that you don’t have to make up your mind at 17 years old on what you are going to do for the next 30, maybe 40, or 50 years of your life. “Navigating college with curiosity and approaching his future with an open mind, Rice discovered a passion that would become his life’s work and save millions of lives.” It gives me some hope, I have ideas of what I want to focus on, but no clue what I want to specialize in.

Lisa Jenkins • Oct 16, 2020 at 2:13 PM

Mr. Paulus said the journalism was “okay” absolutely not. Your writing was fantastic, you draw the reader in and as a reader you forget it’s just a young lady with braces whose writing this piece. You are all very talented and I am thrilled that my son goes to school with all these amazing students. Well Done!