Teens Growing Up More Slowly Than in the Past

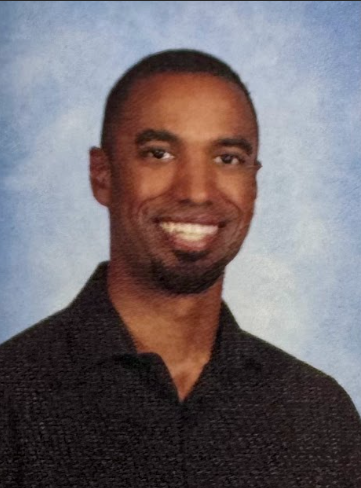

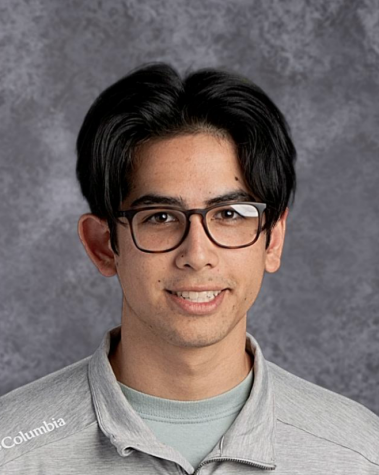

Photo By Sophia Papantoniadias

Junior Sophia Papantoniadias drives to school after obtaining her driver’s license.

Junior Sophie Jennings didn’t get her license when she turned 16 because she was too busy getting her lifeguard credential so she could get a job.

Jennings, who recently turned 17 and doesn’t expect to get license until next spring, is typical of many teens in putting off that milestone of becoming an adult, but she is ahead of many kids her own age in holding a job.

Today’s high schoolers are reaching the milestones of a typical teenager,–having a job, getting their driver’s license, drinking and dating–later than previous generations, according to a study of 40 years of data published last month in the journal Child Development.

Compared to kids who came of age in the 1970s-2000s, today’s teens “are taking longer to engage in both the pleasures and the responsibilities of adulthood,” said Jean Twenge, professor of psychology at San Diego State University and the lead author on the study, “iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy — and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood.”

With today’s 18-year-olds living more like 15-year-olds once did, “the whole developmental pathway has slowed down,” said Twenge.

The study found that 73 percent of seniors across the U.S. have their driver’s license down from 88 percent in 1976. About 55 percent of students have worked for pay, down from 76 percent in the ‘70s.

On a promising note, compared to the early 1990s, 29 percent of 9th graders had sex, down from 38 percent; and 67 percent of 12th graders drank, down from 93 percent. Nationally, 62 percent of seniors had had sex, down from 68 percent in the early 1990s, when that data was first collected.

Generally the young population in the United States seems to be getting older, slower.

The differences are shown in all economic groups throughout the country.

But they’re not entirely due to the demands of homework and extracurricular activities, which is the most popular belief.

Technology and parenting style might play a role in the shift.

“The lure of the internet – which might keep kids glued to screens instead of out driving and dating – probably has had some recent impact and more attentive parenting, sometimes derided as helicopter parenting, certainly has played a role,” Twenge said in a statement with the release of the report.

Growing up in a resource-rich environment also allows kids to slow down, compared to kids who grow up in harsh environments with shorter life expectancy.

Some professionals argue that there are downsides to teens reaching these social milestones later in life. Their principal’s argument focuses on a teen’s ability to exit high school with more work and general life experience. However, teens now are safer than previous generations.

For Jennings, getting a job was an important step in life, while getting a license is not a priority.

“I think it’s important to have a job,” said Jennings, who lives close enough to the pool so she could walk to work. “It shows you are independent and you don’t have to rely on other people.”

Jennings is somewhat out of step with her school peers. An informal survey of about 100 Rio seniors found that students here are slightly more likely to have worked for pay, but they are much more likely than the national average to have a license.

About 80 percent of seniors have a license compared to the 73 percent national average reported in the study. At Rio, 60 percent of seniors said they had a job, compared with 55 percent of 12th graders nationwide who said they had worked for pay.

Students who didn’t get a license when they were 16 said that being able to connect with friends over social media, having parents who are willing to drive and restrictions on licenses for minors played a role in waiting.

“My parents don’t mind driving me and my sister,” said Jennings.

For senior Alyssa Guerra, driving isn’t always necessary to connect with friends.

“There’s so much new technology out there that can get things done for teenagers than there was in the 70s” said Guerra.

Junior Emma Sperber said getting a license does not equal independence as it once did.

“I think that people are reaching these milestones later because they can’t drive anyone until after a year, so they’re not really thinking there is any point to it, especially if their friends already have licences,” said Sperber.

As for fewer teens holding jobs, Sperber thinks heavier school workloads and greater pressure to get into a good college plays a part.

¨For jobs, I think that teens don’t have any time to work because of all of the work they have assigned at school¨ said Sperber.

Junior Drew Murphy had a different take on the trend.

¨I believe that it’s a social norm,” Murphy said. “Kids are pretty lazy and they want to ride on their parents for longer.”

For Jennings, the comparison between this and previous generations, doesn’t tell the whole story of being a kid now, because society has changed so much.

“Everything is so different now,” she said.