Tomine started drawing comics at Rio, now he’s a best-selling graphic novelist

Adrian Tomine’s most recent book, “The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist,” draws partly on his experiences in Sacramento

Photo By Provided by Adrian Tomine

Adrian Tomine’s self portrait

“I had two main goals when I was in high school: to move away from Sacramento and to become a professional cartoonist,” said Adrian Tomine, a best-selling graphic novelist, New Yorker illustrator, and Rio Americano alumnus.

His time at Rio in the late 1980s and early ’90s influenced his work because art for him was an escape from a school environment he describes as an alpha-dominant bullying culture. Rather than try to fit in, he immersed himself in movies at Tower Theater and drawing comics while stealing away time in his favorite class, journalism.

“There were obviously a lot of students who didn’t fit ‘that mold,’ and I have some important memories of people who were smart, generous, and kind,” said Tomine. “I owe a great debt to the fellow weirdos I met along the way who exposed me to a lot of art and literature and music, and who also just showed me that there was a world beyond the social hierarchies of our school.”

Tomine was not immune to wanting to be liked in high school; however, this was hard to achieve when driving a yellow 1973 Chevy Sportsvan.

“Cars were a big deal, and there was a lot of talk about who drove what kind of car,” said Tomine. “I had the embarrassing experience of getting dropped off by my parents for the first two years, and then I had the even more embarrassing experience of driving a yellow 1973 Chevy Sportsvan that backfired every time I arrived in the parking lot.”

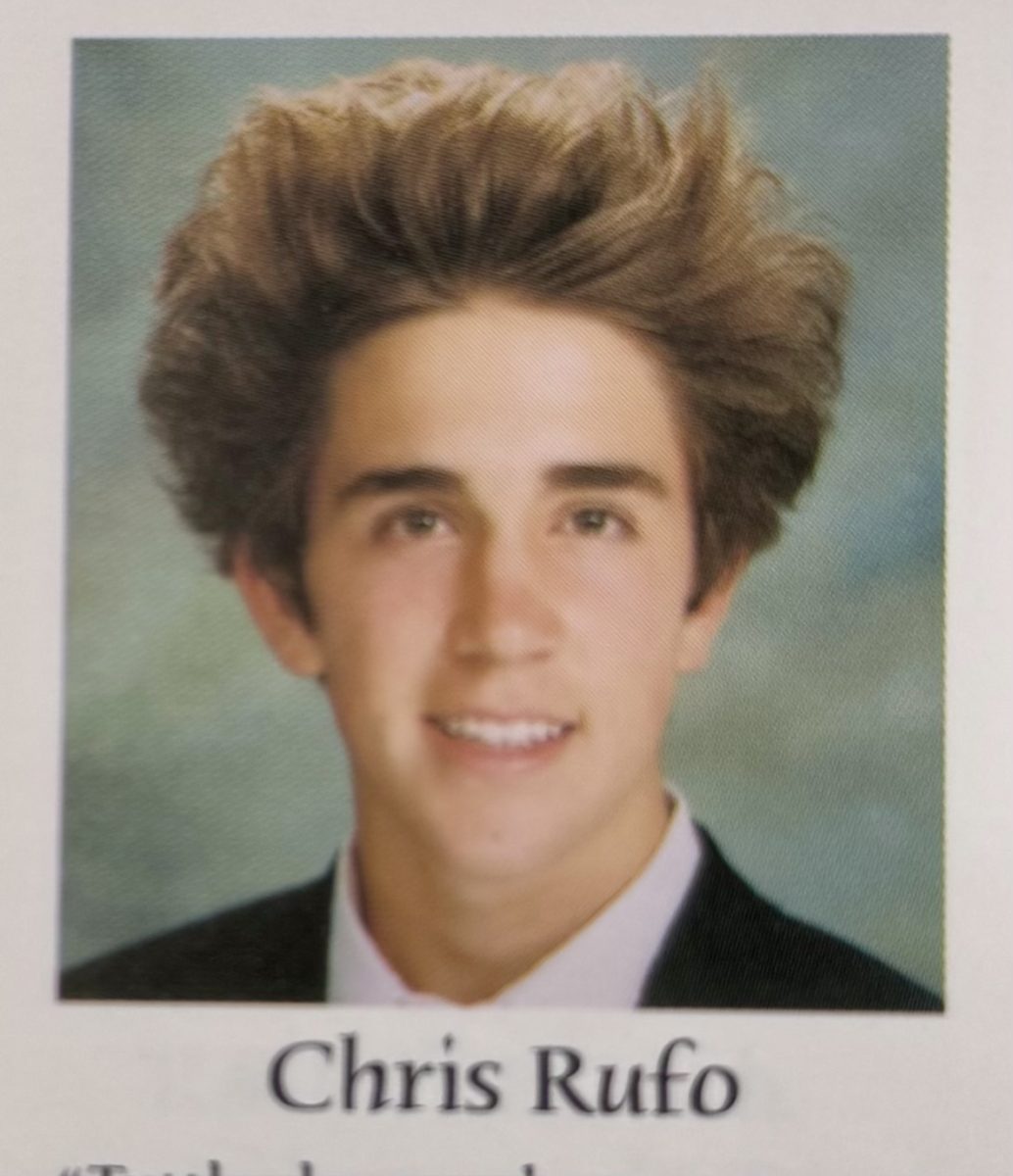

While at Rio, Tomine began to self-publish a comic series called Optic Nerve. The comic is a collection of short stories that he photocopied and sold at school and comic book stores before it was picked up by the publisher Drawn & Quarterly. In 2009 his publisher produced, “32 Stories,” a boxed set of facimiles of the early Optic Nerve mini-comics with an additional pamphlet with Tomine’s Rio yearbook picture on the cover. (In his introduction to the book, Tomine admits to years earlier having begged a fellow cartoonist to remove the photo from his website because posting it was “weird” and “I looked like a real dweep at 17.”)

The series is still growing; however, Tomine says at the moment that he’s more focused on his graphic novels and screenplays.

“It was something I wanted to do before high school, and that same passion carried on long afterward,” said Tomine. “Also, shortly after I graduated, a great comic company called Drawn & Quarterly offered to start publishing my comic for me, so then it became like a real job.”

Tomine was born in Sacramento in 1974 to parents who were both academics with PhDs and who had both spent time in Japanese-American internment camps during World War II. His parents divorced when he was young, and before high school, he moved with his mother to places such as Fresno, Oregon, and Germany, while spending summers in Sacramento with his father.

Sacramento influenced his writing, and he often feels that all of his books take place in an unnamed California town much like Sacramento.

“Sacramento is just inextricably intertwined with my early interest in comics, the beginnings of my career, and the initial longing I felt for a different kind of life,” said Tomine. “I also saw a lot of movies at the Tower Theater, many of which had a huge impact on me as an artist.”

In July, Tomine released his latest book, “The Loneliness of the Long Distanced Cartoonist.” He crafted this memoir, in the same way, he created other works like Optic Nerve, his comic book series, and his illustrations for the New Yorker: in the comfort of his own home in Brooklyn, New York.

“I’ve always worked from home, and that tradition continues to this day, mainly because I’m lazy and I just like being home all day,” says Tomine. “ I have to work in the corner of my wife’s and my bedroom. Unlike most cartoonists, I like to work in a very austere, clean, organized environment, so it’s just the minimum of tools and equipment.”

Looking back on his previous work, Tomine wanted to do something different and push the range of his ability. He also wanted a book for his own expression about being an artist and fitting in.

“A lot of the anecdotes in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist had been rattling around in my brain for years, ” said Tomine. “Then the events that I depict at the end of the book took place, and it all came together in my mind.”

Although the book is about Tomine, his life, and his experiences, readers said that they have been able to connect to his story. He says that’s why art is so important because it can establish a connection with people.

“My main goal was just to make people laugh, mostly at my expense,” Tomine said “But I’ve also heard from some readers that they had a more emotional reaction, especially towards the end of the book, and that’s a great compliment.” says Tomine.

Tomine aspires to help young artists and writers to have faith in their work. Even without a great sense of belonging in high school, or in life after high school, Tomine has seen how impactful art and family can be.

“I think I just had a lot of things I wanted to express about my experience as an artist, as someone who often didn’t feel like he fit in, and as someone who eventually found great happiness and fulfillment in being married and having kids,” Tomine said.

Fitting in has never been Tomine’s thing, and so in this latest book he wanted to reach out to those who have never fit the high school mold. He hoped to make his audience laugh and encourage them to have confidence in their work, and most importantly themselves.

“I think it’s one of the most amazing aspects of art, and I hope people, especially young artists, never feel like their own life isn’t interesting or exciting enough to write or draw about,” Tomine said.

Valeria • Jun 1, 2021 at 1:50 AM

Great story!

Mikhayla O'Kelley • May 23, 2021 at 4:47 PM

I also would love to get onto a field with having something to do with art and enjoyed reading about his story